By Claire Richer

By Claire Richer

Albane Harmange, a 24-year-old with roots in St Barths through her mother, spent a peaceful childhood on the island before heading to mainland France for her studies. Passionate about literature, she chose to enroll in a preparatory literary program at Lakanal High School in Sceaux.

Her curiosity about people and her love for research led her to pursue a career in journalism in Paris. During her apprenticeship at France TV’s Overseas department, she gained valuable experience, graduating in June 2024.

It was during her time as a student that Albane first stumbled upon the topic of slavery in St Barths. Surprised and intrigued, she came across the subject in an article from the Journal de Saint-Barth covering a commemoration event.

She quickly became passionate about this little-known chapter of the island’s history. She found it fascinating to trace the origins of part of St Barts’ population that still lives there today and to bring to light a story that had long remained hidden.

She quickly became passionate about this little-known chapter of the island’s history. She found it fascinating to trace the origins of part of St Barts’ population that still lives there today and to bring to light a story that had long remained hidden.

Motivated by her research, Albane set out to create a documentary, collecting testimonies from experts and working with the limited archives available.

Premiering at the St Barts Film Festival last May, the documentary sparked great interest and curiosity from the public. Albane is determined to continue building on her research, especially by giving a voice to the descendants of enslaved people in St Barts. However, this is no easy task, as few residents have taken the steps to uncover their roots, and the sensitive nature of the subject requires a thoughtful approach.

Here, Albane shares the key insights from her work.

Slavery: The Forgotten Past of St Barths

by Albane Harmange

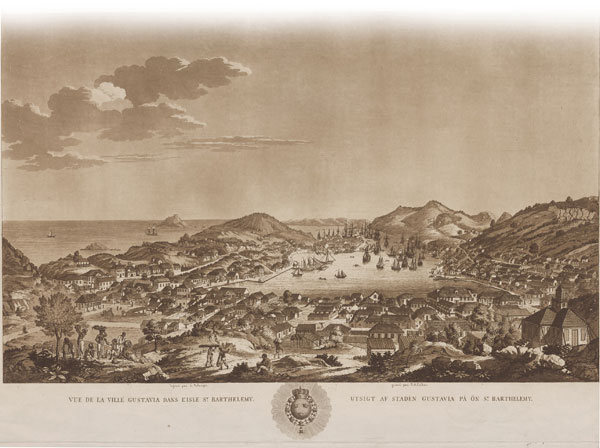

As tourists stroll through the streets of Gustavia, they can take in the remnants of the Swedish period through its distinctive architecture. But do these visitors know that most of these buildings were put up by enslaved people? Most of them don’t, just like many of the residents. It wasn’t until October 9, 2023, during the first official ceremony marking the abolition of slavery in St Barts, that a commemorative plaque was put up under the silk-cotton tree at Fort Gustav III. This location is significant. “It’s one of the buildings built by enslaved people during the Swedish period,” explains Bettina Cointre, the cultural representative of the island’s government.

As tourists stroll through the streets of Gustavia, they can take in the remnants of the Swedish period through its distinctive architecture. But do these visitors know that most of these buildings were put up by enslaved people? Most of them don’t, just like many of the residents. It wasn’t until October 9, 2023, during the first official ceremony marking the abolition of slavery in St Barts, that a commemorative plaque was put up under the silk-cotton tree at Fort Gustav III. This location is significant. “It’s one of the buildings built by enslaved people during the Swedish period,” explains Bettina Cointre, the cultural representative of the island’s government.

During this inaugural official ceremony, the island’s first vice-president, Marie-Hélène Bernier, took a moment to thank one man, Richard Lédée, for his hard work “in bringing out the truth about slavery.“ Thanks to the relentless efforts of this seafarer, October 9 has been set up as the official date of the abolition of slavery in St Barths, replacing May 27, as celebrated in Guadeloupe, a change that’s been in place since 2012. However, in practice, it took time for this new date to really catch on. “It was widely believed that we were mostly white because there had never been slavery on this island,” recalls Richard Lédée. “Our elders were still very much convinced of that and weren’t ready to accept that the history was completely different.”

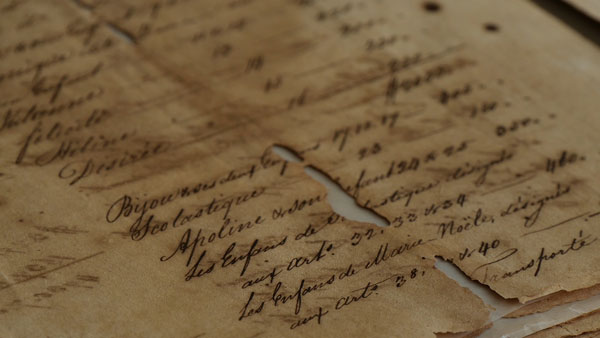

This historical confusion comes from the island’s turbulent past, a small island passed around between various colonial powers, much like many other Caribbean islands. The archives from the Swedish period, which hold information about slavery in St Barths, have also traveled around. When the island went back to French rule in 1878, the Saint-Barthelemy Swedish Archive was sent to Guadeloupe, then to Martinique, and eventually ended up in Aix-en-Provence, at the National Overseas Archives. To save these now fragile documents, Swedish historian Fredrik Thomasson and his team took on their digitization. “This fulfills the true purpose of archives, which is to make them available to the public,” says Elise Magras, head of the St Barts archives.

This historical confusion comes from the island’s turbulent past, a small island passed around between various colonial powers, much like many other Caribbean islands. The archives from the Swedish period, which hold information about slavery in St Barths, have also traveled around. When the island went back to French rule in 1878, the Saint-Barthelemy Swedish Archive was sent to Guadeloupe, then to Martinique, and eventually ended up in Aix-en-Provence, at the National Overseas Archives. To save these now fragile documents, Swedish historian Fredrik Thomasson and his team took on their digitization. “This fulfills the true purpose of archives, which is to make them available to the public,” says Elise Magras, head of the St Barts archives.

However, some island residents didn’t wait for these documents to go online to start looking into this lesser-known part of history. Arlette Magras, co-founder of Domaine Félicité, shows numerous documents in this family museum that prove the presence of enslaved people on the island. One such document is a census carried out by Samuel Falhberg in 1785, listing the “Whites” and “slaves” in each neighborhood of the island. “There were even times when enslaved people made up the majority,” highlights Arlette Magras. If you look carefully, there are still traces of this forgotten past scattered across the island.